Quest for The Cosy

The challenge was simple: find out what was screening at the Cosy Cinema, Kings Heath during its brief existence, then find a copy of one of those films and screen it again for a 2025 audience.

How I wrote ‘111 Places in Birmingham That You Shouldn’t Miss’

Does Birmingham have a unique and identifying cuisine? Not really. Baltis are essentially quickly-cooked versions of long-existing curry recipes, served in vessels originating elsewhere. Chocolate, custard and other industrialised foodstuffs don't count as cuisine, nor does Mr Egg.

A Journey to Avebury

A few years ago, I started thinking about Derek Jarman’s short film A Journey to Avebury in terms of the actual route taken…

Don't Look Now... fate gifts me a trip to Venice.

What to do with five hours in Venice, that watery anti-Birmingham?

Two Gray Days in Glasgow

In 2019 I had falsely believed that Gray was no longer (to quote my late mother) 'compass mantis’ and had long ago ceased production of words and pictures. Encountering an interview with Gray in my online feed revealed him to be in advanced years and confined to a wheelchair, but lucid and actively translating Dante.

Spaceplay for the Win

Survival instinct engaged, I hacked the tin of curried beans open with a screwdriver and heated them up on a portable hotplate that I had in my studio. I went back to work, hotplate serving as a radiator to the enormous space. By late evening, I was freezing and hungry again and went to look for more food. A second sweep of the floors turned up only cinnamon ‘Winter Warmer’ Tic Tacs and a carton of Ribena. I felt the urgent need to leave and resolved to escape.

‘Fleas Do Not Smoke’

Joel Lane levels off and the houses come closer to the pavement. ‘Loughrigg 1682 cottage’ (as the plaque reads) is as rugged as its Cumbrian counterpart. This was the home of Hyde mayoress Kathleen Grundy, who early one morning in 1998 was killed by a fatal injection of diamorphine administered by her doctor. It was the final (or rather, the penultimate) killing by ‘Dr Death’: a nickname that Shipman acquired before, not after, his arrest.

Unravelling Plymouth Labyrinths

Later in my Plymouth excursion, I experience the Fractal Harbour Illusion. A walk to the other side of a harbour often involves misjudging the distance. The unreadable scale and irregular shape of bay with various unexpected and uncrossable inlets mean you may end up walking between three and nine times the distance you expected. The Harbour Illusion is a labyrinth that has caught out unwary Mancunians, Brummies and other land-locked lubbers throughout history. To solve it, simply keep the sea to your left and eventually you will emerge.

Street Gym - Reclaim the Streets

Bicycle racks, railings, low level walls, stair cases and public art all become open-access gym equipment to the Street Gymnast under John’s guidance. Responding to bollards, borders, patterns on the ground…we were children the last time we paid attention to our environment in this way. Before there’s time to get bored, or when security arrives, you are moving onto the next obstacle.

Photo credit: Lisa Brown

Sour Grapes

But the Fox and Grapes was an important piece of Birmingham history, as it represented the last building standing from Birmingham’s early days as a pre-industrial revolution market town. It was on the first map of Birmingham, drawn up in 1731 by William Westley—or rather the building that later became the pub. Now this listed building has mysterious burned, ahead of HS2’s arrival in September 2070.

Knot Working

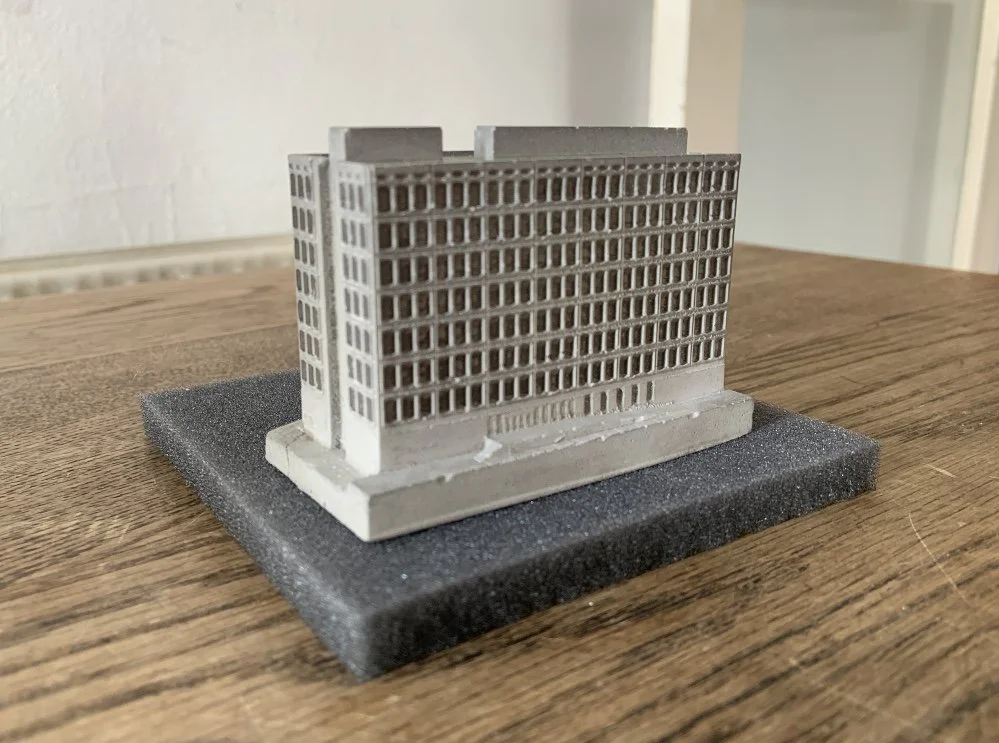

The signpost looked unusually scruffy, even in the context of a civic centre that is essentially a building site. The clear plastic weather-proofing stuck over the signs is badly perished and peeling. The post itself looks like it was recently hit by something heavy, and now lists dramatically, like its square companion the Iron: Man. Closer inspection reveals that many of the destinations the arms point to no longer exist, making its primary function redundant.