Two Gray Days in Glasgow

Back in October 2019, I devised an afternoon’s walk round Glasgow’s West End in search of the murals of Alasdair Gray. I was prompted to do this by a jarring but delightful discovery: for the longest time, I had falsely believed that Gray was no longer (to quote my late mother) 'compass mantis’ and had long ago ceased production of words and pictures. A chance encounter with an online interview revealed him to be in advanced years and confined to a wheelchair, but lucid and actively translating Dante, while working on images as restrictions allowed. It felt like a spectre has become flesh again. Gray had been such an important discovery in my teenage years: an older Glaswegian friend (Bill Slimmond, raised in Paisley) recommended I read Lanark while we were both studying on the same art foundation course in Manchester. When I returned Bill’s book, he insisted I should keep it as I would want refer to it again, or to lend it out myself. Not only did I do exactly that, I read all the other Gray titles that were available in 1989, and even wrote my own (unfinished) strange story of hallucinatory workplaces, class conflict and colourful glass vessels filled with sweet, sticky alcohols. That story remains vivid but is confined to now unreachable computer disk medium, and it is better that it stays there.

I met him once, and by ‘met’ I mean we existed together briefly, near the same table Birmingham. In 1996, Mavis Belfrage was freshly published and my local art centre hosted a Q&A during the city’s Literature Festival. A key element of the festival’s extensive programme required Gray to be shown to his seat and advised on the availability of chilled drinking water on a nearby low table. I was delighted to be selected to take on this important responsibility, which was carried out efficiently and, I felt, wittily and elegantly.

In 2017, my friend Adriana had relocated from Brum to Glasgow, and I arranged a visit, inspired by Gray’s revivified presence in my mind. We drank at the darkly cosmic Oran Mor, its epic ceiling fresco surely Gray’s masterpiece (Adriana later was married there), ate at The Ubiquitous Chip restaurant, which features several of Gray’s curiously collaged wall paintings and then took the underground back home from Hillhead, which is surely the AG mural most familiar to Glasgow citizens. Earlier in the day I had visited a small tiled floor at a swimming baths, the depicted swimnasts there bearing Gray’s signature style. Adriana had seen his work around the city, but not connected them.

At The Ubiquitous Chip (an ironic reference to the standard plate-filler; one which is never seen at The UC) I thought of a more ambitious city walking tour I’d like to do, which combed the city for further Gray moments, as presented by fact or fiction. It would require a comprehensive revisit of his stories, pictures and places, and would reveal patterns invisible to the remote reader. The city would be the catalyst to reveal that lost layer. His stories straddle worlds as standard and I loved the idea of a real-world guided tour that regularly dipped into fiction. Gray’s stories are often set in named and identifiable places, even providing specific addresses, which has the effect of anchoring an imaginative or even outlandish story; making the fantastic seem more real. Unlike literature’s various unreachable towns of Arkham, Barchester, Casterbridge and Castle Rock, Gray allows his fictions to be presented as real. While we talked (Adriana and I) I sensed Gray may appear at any moment, knowing he lived locally and that this restaurant was a favourite. That possibility fuelled lively thoughts, though I would likely have only issued a cheery wave.

Two things yanked the reins of this galloping steed to bring it to a screeching halt: the sad death of Alasdair Gray just a few weeks later and, a few weeks after that, covid-19. All my various walking plans were shelved, but in their place, long dormant desires were allowed time and space, light and water. I researched and wrote my first book (a guide book to Birmingham: ‘111 Places in Birmingham That You Shouldn’t Miss’) and my first published work of fiction (‘Cup Song’ in the anthology Digbeth Stories). The imaginative use of cities, as practiced by Gray, absolutely informed my writing for both of these factual and fictional works.

Years later, the Alasdair Gray citizen’s walk is real, being the vision of Rachel Loughran and with the walking tour being devised by Rachel Cochrane-Slocombe. On the verge of a cinematic release of Poor Things, filtered through the surreal heart of Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster, The Favourite), Glasgow is claiming back the now drearily predictable London setting of Gray’s 1992 Victorian sci fi comedy-fantasy, which by now has a genre to identify it: Steam Punk, or perhaps PoMo Steam Punk. This is a self-guided tour that visits key places from the book and invites you (more or less) to read along in the manner of a loved and familiar film or musical. Has this ever been attempted before?

The scale is ambitious, even epic. The introduction suggests 2 - 2.5 hours across three separate city zones, but I think only the most competitive and sporty of Gray’s fans will complete the journey in this meagre time. I allowed myself two days to explore the city at leisure and select from the most intriguing of the annexed optional extras. The suggested order of the walk is: East End > City Centre > West End, perhaps to reflect reading a page from left to right, but I did not follow the route sequentially: more like the ‘flashback’ narrative of Lanark. I was meeting another friend for lunch at the University and so decided to start there. Alas, it was Ken’s first day at a new job at UG so he couldn’t join me for the walk. After I gifted him Lanark following a move from Birmingham to Edinburgh in 2018, he too had become a keen Gray reader.

I arrive via Hillhead station, where an amazing mural by Gray of the area was installed in 2012. A pigeon’s eye view allows a good sense of how the local land lies… and this was Gray’s domestic domain since 1969. Buildings and streets are faithfully rendered and labelled in Gray’s distinctive ‘wedged’ lettering (the ‘Gray Display’ font) with the occasion wry caption and comment. The network of streets is bookended by grids of illustrations of the real and imagined. Here are ‘All Kinds of Folk’: Urban Foxes, Fiery Dragons, Lucky (white) Dogs, Bonny Fighters, online Culture Vultures (their talons clutching at mouses) and the Sharp Stingers: a pair of poised scorpions, one of whom we will meet again.

Hundreds, thousands see daily (or at least walk past) these lines:

Do not let daily to-ing and fro-ing

To earn what you need to keep going

Prevent what you once felt when wee

Hopeful and free.

The whole work looks like it could fold into a book jacket for an imaginary or yet-to-be-published codex of works. The mural is behind the turnstile but if you aren’t travelling by underground, you can ask to be freely admitted to see the mural.

On then to the University, where Archibald McCandless studied as a medical student in 1879. Head to the main gatehouse rather than the modern medicine block for a more authentic setting. In the foyer, a collage of Glasgow extracts includes an illustration by Gray, where she is moping around on a staircase with a likewise listless ivory king.…she looks familiar but I couldn’t quite place her! I nod politely in case it later turns out I do know her [note: it is still a mystery]. My G trip coincided with Scotland’s hottest day —27 degrees!— and so lunch with Ken was a picnic in Kelvingrove Park, also on the walk route. The river Kelvin flows through the park, forming a wooded, natural valley, giving the impression of being much more rural than its true metropolitan setting. Without really trying, we find the Loch Katherine Memorial Fountain. The stonework features carved fauna and flora, but in recent years real ferns now grow straight from the stone work amongst the gannets, owls, centaurs, fish and other real and not-real beasties. A welcome revelation is the scorpion, curled over ready to sting, to be found in an upper roundel of the fountain, perhaps with some lost heraldic meaning and possibly this specimen collected by Gray, for display in his Hillhead mural. Several people have thrown in lucky coins amongst the algae, others vocalise their wishes aloud that the fountain be repaired (it was last active during Glasgow’s City of Culture era c 1990). Until that repair happens, a cheeky pair of enterprising weans collect the coins, sparkling through the water in the noon sun, in a seaside bucket brought for the occasion.

The river, fountain and park are backdrops to the story, and referenced in footnotes, rather than featuring key events from the Poor Things narrative. Further along the route is a specific address that is pivotal to the story. 18 Park Circus is the prestigious residence of Dr. Godwin Baxter, and the location of his secret experiments in reanimating the dead. Not a stone is or leaf is out of place on this crescent of fashionable townhouses, but counter this civic scene with a stroll along the service alley (or ‘tradesman’s entrance’) of Park Terrace, a more humble domestic vantage and, what’s more, scene of a hotly contested coach house in the novel’s later thorough, fussy (and fictitious) footnotes and references. The houses are dominated by the suitably gothic towers of Old Trinity College and Park Church Tower, and for me this is a highlight of the walk. The routes allow some flexibility and indeed the official order further suggests extra locations to optionally drop in, so I don’t feel I’m missing a particular narrative arc by spending the rest of the day at the Kelvingove museum, glad to be out of the sun. For the infrequent visitor to Glasgow, the draw is too great. Lansdowne United Presbyterian Church, scene of the thwarted and confused marriage between Bella and Archibald, dominates all of these streets. When you visit it, you will realised you saw it many minutes previously.

My hotel is next to the School of Art, where Gray studied from 1952 to 1957, and now encased in scaffolding. On the way back, I dip into the degree show exhibitions by architecture and interior design students. The young creatives I chat to there don’t know Gray’s work but have heard of the forthcoming Poor Things, such is Lanthimos’ current rising star quality and are glad to hear of the link.

I leave my luggage at the station the next morning, then head out to St Andrews Suspension Bridge, location of one of the book’s darker moments: the suicide of the woman who becomes Bella (I am merely hinting at the story’s plot points and navigating around spoilers: the creators suggest you already have familiarised yourself with the novel before tackling the walk). The story is a work of fiction —obviously but also not so obviously— and the suicide is a key plot point, but nevertheless the bridge visit may bring to mind all real watery deaths and sad ends. When I visit, there is a nearby fresh floral and photographic tribute to ‘Brian’. The bridge in fact and fiction allows the work of the Glasgow Humane Society to be told: the bridge is dedicated to the memory of Ben and Sarah Parsonage; the unassuming boatman rescued more people from drowning than anyone in Britain. The nearby lodge was theirs, planted with sculptures, canoes and cherry trees to further their memory.

Perhaps the bridge was chosen by Gray for its proximity to the People’s Palace, where he once worked as ‘city recorder’ and his portrait work is still exhibited there today. Gentle sketches, loose interiors, playful perspectives and collage-like assemblies offer informal glimpses of the civic dignitaries and key city figures of the 1970s. An opulent, perhaps overwrought fountain outside depicts figures and animals associated with Victorian Empire - an Eastern twin to the Loch Katherine fountain of Kelvingrove Park. ‘This terracotta fountain is the largest and best example of its kind in the world,’ brags a sign, but the fountain sure could do with a clean. The park here is generous and expansive but doesn’t have the mixed terrain of Kelvingrove. The former Templeton carpet factory, now empty, is a striped spectacle worth a quick glimpse.

The walk to the Necropolis, in search of the McCandless tomb, passes through domestic residences and the gigantic Tennent Caledonian brewery. On the way, look out for the paired castle-like buildings when you reach Gallowgate, one swallowed up by a low level housing estate. They invite a folk story to be invented to explain their connection and survival. Maybe there is a clue in the street name.… Devise that story as you pass the Caledonia brewery, with murals celebrating Tennent’s advertising down the decades, including the famous Lager Lovelies of the 1970s—and their recipes for potato scones.

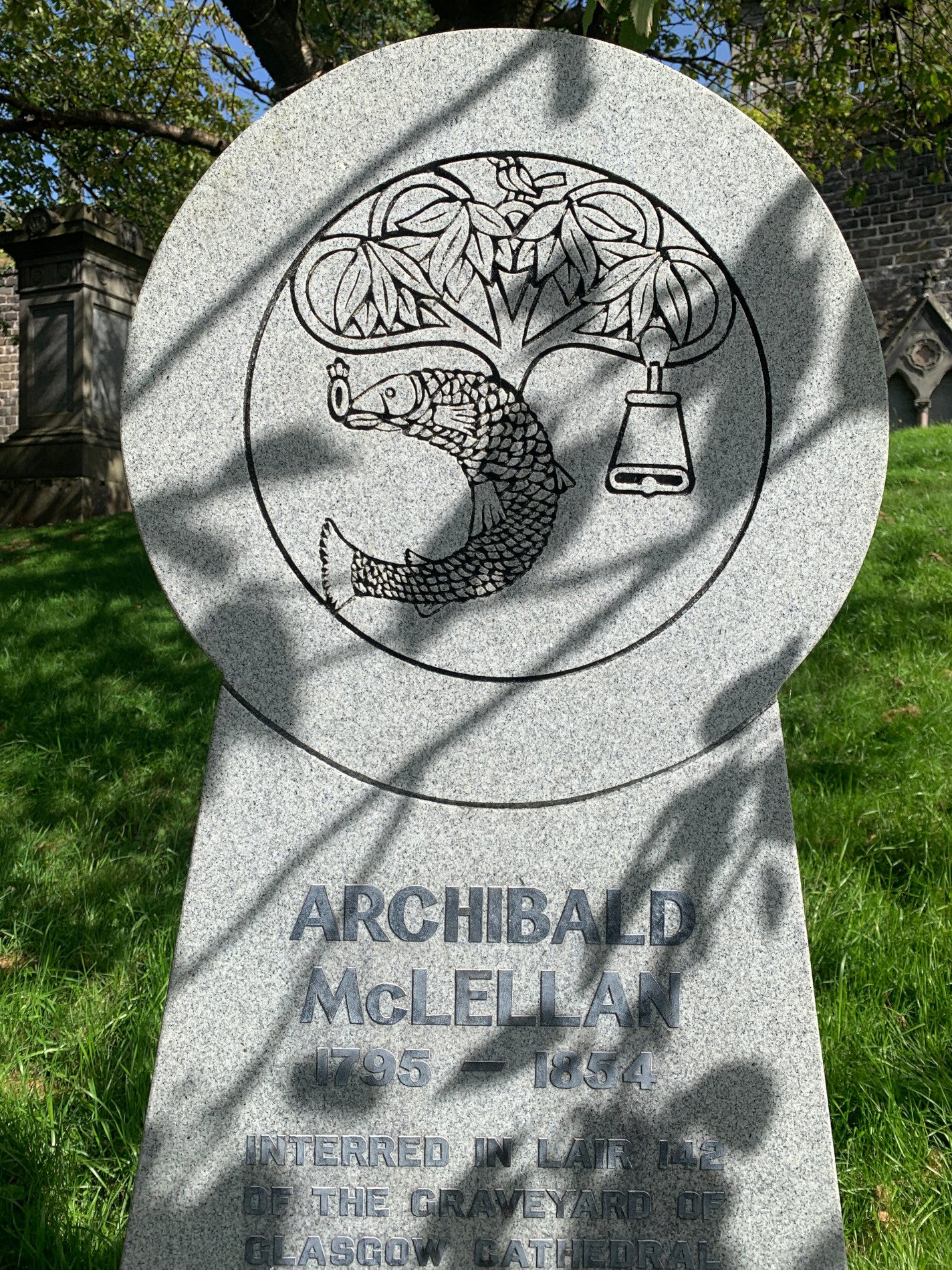

The path to the tomb is one of relentless ascent, with some red-herring paths to beguile the less familiar visitor. One headstone spoke to me; an illustration of surreal Glasgow’s coat of arms, which seems very much like Gray’s own bold line drawing style.

There’s a tree that never grew, There’s a bird that never flew, There’s a fish that never swam, There’s the bell that never rang.

It is true that for two days, all heraldry, all rampant leopards, dragons, cats and dogs have taken on his clean, bold style. Archibald (McLellan) is the name on the grave… it would not be the first time a graveyard inspired character names for a writer. On conquering the summit, I lie on the sunlit uplands beside the Monteath mausoleum. No name or text of any sort is recorded there, meaning it can fictionally assume another identity: in Poor Things it is the Baxter family tomb. By good fortune a tour group arrives and relates the (real) history of the tomb; easy, passive and supine research for me. I learn that the noduled stonework actually features the heads of leopards, now weathered and gnarled but just about recognisable as such when I find my feet, fifteen minutes later.

For the final chapter of the tour (or second if you are doing them sequentially), I headed straight to GOMA—Gallery Of Modern Art — where there are Alasdair Gray works in the Domestic Bliss exhibition in gallery 4 (on for years, it seems). This was formerly the Glasgow Stock Exchange, mentioned in the book along with the Theatre Royal, Glasgow Art Club, Sauchiehall Street and more… I feel certain I’ve visited all these on my various Glasgow visits. The two that intrigue me this afternoon are the given address of Duncan Wedderburn, who lives at 41 Aytoun Street, some way out in Pollokshields, and the Alasdair Gray Archive itself. The Archive, I notice, requires some advance notice ahead of a visit which I assume is more than my available hour and a half. Accordingly, I Uber to the address (in reality, it’s Aytoun Road, perhaps a disguise) vowing to return to the archive with a more comfortable schedule. It’s a smart residential address in Pollokshields that would be an hour’s walk away were you to do it. I like it’s inclusion in the official itinerary, another element to make the strange story real. I also enjoy ending up in a part of town I’d be unlikely to visit otherwise — it feels like somehow challenging fate, or at least challenging the destinations that Glasgow might otherwise hand me. There is time to stroll back to the station in the still-warm late afternoon, even against the impossible-to-cross. Part of me, I feel a week later, is still in Glasgow, waiting to cross the road.

And then it’s all done. A beautiful landscape is revealed out of the window as I head back through Cumbria to Brum, eventually too dark to see anything but myself.

The walk info is here:

https://www.poorthingsnovel.com/poor-things-tour-/

…while the comprehensive Poor Things novel guide is here:

https://www.poorthingsnovel.com/

…and the even more comprehensive Alsdair Gray Archive site is here: